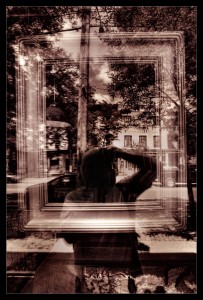

The photographic image captures a segment of what is in front of the camera, but the viewer senses that what is shown is simply a crop of a much larger scenario.

The framing of an image is a border of sorts. To a degree, it defines what the photographer wants you to experience. But the frame also has an implied extension that goes beyond what is visible. In more ways than one, the frame is a portal into the deeper intent of the photograph. We might think of it as a frame of reference.

A great photograph has what is called an extended frame. By extended, I mean that the image implies that the world shown in the image includes things that are not seen in the image. It implies that the landscape is similar, the room is bigger, and the sky is larger than what might be shown. It also implies that the larger backdrop of the subject environment sets the colors, tones and mood. We experience the image by imagining a similar world that is bigger than what is captured. We know that what we are seeing is only a slice of what was there to see.

A photograph can imply as much about what is outside the frame as it does with what is within. We read images based on our past experiences of similar situations and what we might know about the nature of subject. That holds true with how we imagine the extended frame. The extended frame is what we use to base a setting for the things shown.

The landscape is probably the easiest type of photograph to realize what I mean. We tend to believe that the world shown is equal to the world that is not. We believe it for at least in relation to the world within close proximity to what we see in the frame.

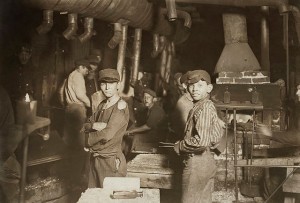

Sometimes, the extended frame can also become what we imagine about the subject itself.

When we look at the Lewis Hine images of child labor for example, we not only see the faces, we sense the dreadful conditions of the factory or the mines where they worked as well as all the similar faces in the same kinds of situations that are not included. We also might think of their families, the circumstance of the rest of their lives or the society that allowed this kind of thing to happen.

In another example, we might look at a portrait of someone’s face. Depending on the nature of the portrait, we might begin to see physical traits that imply certain characteristics we associate with such things as aging, beauty or pride. In realizing this we might begin to imagine the life that this person has lived. We may also begin to think about that person from what we might already know about them or through any possible clues provided in the image. Such things as clothing or what the subject is holding may lend some insight. But we might also consider the inner persona that is implied by the image through facial expression, the eyes, the environment where the portrait was taken or any of many other possible indications. This implies a framing that exists within the subject itself. It is an implied framework that helps us to define what we are looking at in the image. It is an inner framing.

It can also be true that what is in included in the frame can be altered by what is left out. In other words, what we choose to include may not carry the same reality as what we may have excluded from the shot.

For example: When we choose to frame an image, it is easy to frame (crop) out those details that we find conflicting or distracting. Sometimes however, those details may be more truthful to the thing we are photographing. In which case, it just might be more honest to include them as a way to see the true reality of the subject.

An example of this might be when we step over or look past those details in the environment that clutter what we would like to photograph. Such objects as a parking lot, road signs, old tires, or an overturned oil drum. By including the details into the image, rather than cropping the picture, we can produce a more realistic image of the situation. You might consider this as a way of giving context to an image, which otherwise offers little or nothing.

Of course, we all want the world to look pristine and it is usually pretty easy with modern zoom lenses to shoot right past these kinds of details. The photographer has a choice to do so if he/she chooses. The problem however, as I have tried to show here, is that your audience will never know the true reality that you do not include within the image. They instead believe that what you show them is consistent with what you did not. They will accept what they see as something they can extend beyond the frame within their imaginations. They imagine things that simply are not true. That part is what can prevent us from realizing the truth of your subject.

While there are countless images that show us what the photographer wished to see, there are fewer that show us enough to reveal the reality of the world we actually live in. And although the world has respectable beauty that we can still find, we should also be made aware of how it is treated and disrespected. To understand the reality is a first step toward change. It is the first step in making the world more like what we want it to become.

And for all you viewers out there, the photograph can be looked at in a number of ways. However, be suspicious of images that look a bit too perfect. Never take an image at face value. It is very likely that it does not represent everything the subject might be about. It may not show you truth at all. It is also likely that it will show you little of the actual place where it was taken.

To understand an image, you need to rely on what you see inside the frame and what the image suggests about the subject. The rest is up to what you believe you know, as well as what you might imagine.

You can read about my book “Rethinking Digital Photography” here.

Please have a look at some of my other posts here.

NOTICE of Copyright: THIS POSTING AS WELL AS ALL PHOTOGRAPHS, GALLERY IMAGES, AND ILLUSTRATIONS ARE COPYRIGHT © JOHN NEEL AND ARE NOT TO BE USED FOR ANY PURPOSE WITHOUT WRITTEN CONSENT FROM THE WRITER, THE PHOTOGRAPHER AND/OR lensgarden.com. THE IDEAS EXPRESSED ARE THE PROPERTY OF THE PHOTOGRAPHER AND THE AUTHOR.